Table of contents Link to heading

- Table of contents

- Intro

- History

- Python - dynamically typed language

- Type hinting, type annotations, type checking and data validation.

- Why to use type hints

- Simple Types

- Type checkers

- Beyond basics

- Generics

- Abstract Base Classes

- Protocols

- ABC vs Protocols

- Problems

- Other typing features

- MyPy Misc

- References

Intro Link to heading

This article is about Python type hints. You will learn what type hints are and how to use them. While explaining type hints, I will also explain some other basic Python concepts.

All the examples use Python 3.10 (but sometimes I will show how certain things look in other versions), and mypy 1.18.1 (if you don’t know what it is, you will find the explanation later in the article).

I intended to reach a broad audience, both beginners and experienced programmers. That’s why the post starts from the very basics and slowly moves to more advanced subjects. If you are a beginner, don’t worry if at some point you start losing track of what is going on. You can always return here later once your skills increase. If you are a more advanced user of Python, you can skip ahead immediately. Although I recommend going in order, as in some sections I’m referring to previous ones.

There are a couple of things that you will not find here. Due to the article’s length, I had to remove the chapter about narrowing types and usage of stubs. You will find those topics in upcoming separate posts. I will also not cover the topic of invariance, covariance, and contravariance.

History Link to heading

When preparing to write this blog post, I decided to dig into the history of types a little bit. To my surprise, something that I took for granted was not that obvious in computer science for a long time.

According to an Arcane Sentiment post, the term “type” was not introduced in programming languages until 1959 in Algol. The first “type-like” term occurs in 1956 in Fortran, but something that we know nowadays as types was there called “mode”.

In 1967 Chris Strachey created an influential set of lectures “Fundamental Concepts in Programming Languages” where he talked about types.

And in 1968 James Morris applied type theory to programming languages.

So now things are getting interesting. Because it appears that type theory is something ancient that predates even computers by decades. Between 1902 and 1908 Bertrand Russell created a type theory for mathematics.

Nowadays, type theory is an academic study about type systems. And the type system is the set of rules that creates a relation between types (string, integer, float, etc.) and specific terms - in the case of programming languages, variables, parameters, arguments, etc.

At the very end we have data types. Because I cannot paraphrase well what a data type is, here you have a quote from Wikipedia.

In computer science and computer programming, a data type (or simply type) is a collection or grouping of data values, usually specified by a set of possible values, a set of allowed operations on these values, and/or a representation of these values as machine types.

But what is the type for us, and why do we need (or don’t need) them at all? Once types finally got popular in programming languages, they had a few purposes.

For example, let’s look at this small C program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int smallInteger = 42; // declaring a small integer

printf("Value: %d\n", smallInteger);

return 0;

}

The smallInteger in memory it looks like this:

+----------+----------+----------+----------+

| byte 1 | byte 2 | byte 3 | byte 4 |

+----------+----------+----------+----------+

| 00000000 | 00000000 | 00000000 | 00101010 |

+----------+----------+----------+----------+

So knowing what data needs to be stored, the program can allocate the necessary amount of bytes for it. In this example it is four, but for longer integers it can be 8, 16, 32, or even 64 bytes. Back in the day, when resources in computers were very scarce, this was very important.

A second reason for using types is operation safety.

def greet(name, age):

return "Hello, " + name + " You are " + age + " years old."

message = greet("Alice", 30)

# Outputs:

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<python-input-1>", line 4, in <module>

# message = greet("Alice", 30)

# File "<python-input-1>", line 2, in greet

# return "Hello, " + name + " You are " + age + " years old."

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~

# TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

Python throws an error because it does not know how to reasonably perform an operation on adding the number “age” to the string. In other words, how to change the bytes in memory so it stores the data correctly*.

* That’s not entirely true, more about this later in the article.

Python - dynamically typed language Link to heading

Programming languages traditionally divide into dynamically typed and statically typed languages. In dynamically typed languages, the type of the variable is evaluated at runtime, not beforehand like it happens in statically typed languages.

Statically typed languages would not allow for such an operation at the compilation level, because they would detect that there is a type mismatch and the operation cannot be permitted.

But Python works a little bit differently. Not only does it check the type during runtime, but it also executes the code and then throws an error. The fact that in the previous example there is an error is because the implementation of the int and str objects does not allow for such a use case. But this comparison does not happen on the “type” level - as there is no such thing as an internal type that needs to match. It happens because both int and str implement the __add__ method, where it checks during runtime if the type of the other object allows for addition.

Purely academically, because I see no practical use for such a case, we can create our own int and str objects that allow for such behavior:

class Int(int):

def __add__(self, value: int | str) -> str | int:

if isinstance(value, str):

return str(self) + value

return super().__add__(value)

class Str(str):

def __add__(self, value: int | str) -> str:

if isinstance(value, int):

return self + str(value)

return super().__add__(value)

my_int = Int(5)

my_str = Str("Hello")

print("Is Int type of int:", isinstance(my_int, int))

print("Is Str type of str:", isinstance(my_str, str))

print("Type of Int:", type(my_int))

print("Type of Str:", type(my_str))

print("Adding Int to Int:", Int(5) + Int(5))

print("Adding Int to Str:", Int(5) + Str("World"))

print("Adding Str to Int:", Str("Hello") + Int(5))

print("Adding Str to Str:", Str("Hello") + Str("World"))

# Output:

# Is Int type of int: True

# Is Str type of str: True

# Type of Int: <class '__main__.Int'>

# Type of Str: <class '__main__.Str'>

# Adding Int to Int: 10

# Adding Int to Str: 5World

# Adding Str to Int: Hello5

# Adding Str to Str: HelloWorld

And that code works. We can see my_int is of type Int and my_str is of type Str. And we can perform addition between Int and Str.

Duck typing Link to heading

If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck it is a duck.

Duck typing is partially related to types. In Python everything is an object.

You should also know that when Python tries to access an attribute on an object, it does not care about that object’s type, only if that object has the specified attribute.

For example, in the code below, when animal.speak() is being executed, Python searches for the attribute with that name on the class, and if one exists, it tries to call the object that is related to such an attribute - in this case a method object.

class Dog:

def speak(self):

return "Woof!"

class Cat:

def speak(self):

return "Meow!"

def animal_sound(animal):

# We don't check the type of 'animal', just call speak()

print(animal.speak())

dog = Dog()

cat = Cat()

animal_sound(dog) # Output: Woof!

animal_sound(cat) # Output: Meow!

In this example it doesn’t matter what class is being passed, as long as it implements the speak method. We could create a MagicCar that implements speak, and it will work.

This might sound crazy, but in fact it is the core feature of Python. It allows for a lot of flexibility. But it can be a problem when the passed object does not have the required method implemented.

EAFP vs. LBYL Link to heading

If we create a class Car that uses honk instead of speak, then we receive an attribute error.

class Car:

def honk(self):

return "Beep Beep!"

def animal_sound(animal):

# We don't check the type of 'animal', just call speak()

print(animal.speak())

car = Car()

animal_sound(car)

# Outputs:

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<python-input-0>", line 10, in <module>

# animal_sound(car)

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^

# File "<python-input-0>", line 7, in # animal_sound

# print(animal.speak())

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^

# AttributeError: 'Car' object has no attribute 'speak'

How can we handle that? Obviously, we could use type hints and run a static type checker so it shows the error, but that is still ahead of us. Now we want to prevent errors during runtime.

There are two approaches: EAFP (Easier to ask forgiveness than permission) and LBYL (Look before you leap).

# LBYL example

def lbyl_animal_sound(animal):

if not hasattr(animal, "speak"):

print("Object cannot speak!")

return # return just to break from the function

print(animal.speak())

# EAFP example

def eafp_animal_sound(animal):

try:

print(animal.speak())

except AttributeError:

print("Object cannot speak!")

dog = Dog()

car = Car()

lbyl_animal_sound(dog) # Otuputs: "Woof!"

eafp_animal_sound(dog) # Outputs: "Woof!"

lbyl_animal_sound(car) # Otuputs: "Object cannot speak!"

eafp_animal_sound(car) # Outputs: "Object cannot speak!"

EAFP is generally considered to be more Pythonic, due to the dynamic nature of Python. But which approach to take depends on the situation. Raising an error consumes more resources, but performing an every time check in an if-statement also takes some time. Generally the rule of thumb is to use EAFP when we don’t expect to raise an exception often, because in such cases we don’t waste time on if-statement checks. But if we expect a wrong type or object to be passed often, then raising exceptions would consume a lot of resources, and it is better to use the LBYL approach with if-statement checks.

Type hinting, type annotations, type checking and data validation. Link to heading

Before talking more about types and type hinting, we need to make a small distinction about what type hints, type annotations, and type checking are.

Type hinting refers to all sorts of information about the types in the program. These can be inline comments (now deprecated) right next to the variable, parameter, or function. But types can also be part of the documentation string - in Python called “docstring”.

Annotations are a sub-type of type hinting that refers only to the special syntax, where we write the type of the parameter or variable after a colon. And after an arrow symbol “->” and before the colon in the function to show what type it is returning. Because of that, type hints and annotations are often used interchangeably.

It is worth mentioning that annotations were introduced in Python 3.5 with the famous PEP-484.

Example of type hints and annotations.

from typing import List, Optional

def multiply_elements(

numbers: List[int], # parameter with annotation only

factor: Optional[int] = None # parameter with annotation only

) -> List[int]:

"""

Multiply each number in the list by a factor.

Args:

numbers (List[int]): List of integers to multiply.

factor (Optional[int]): Multiplication factor. Defaults to 1 if None.

Returns:

List[int]: The list of multiplied numbers.

"""

# Using inline type comments for local variables instead of annotations

if factor is None:

factor = 1 # type: int # default factor set here

result = [num * factor for num in numbers]

return result

# Inline type comment for a variable before use

values = [1, 2, 3, 4] # type: List[int]

multiplied = multiply_elements(values, factor=3) # type: List[int]

print(multiplied) # Output: [3, 6, 9, 12]

Type checking is a process of static analysis that verifies whether the types are correctly written in the code. It does not impact the program runtime. This means that a program can fail the type check and still run correctly.

The following program has wrong types but it will still work:

# Someone confused types of name and age, and leave None as a return type

def greet(name: int, age: str) -> None:

return f"Hello, {name}. You are {age} years old."

message = greet("Alice", 30)

print(message) # Output: Hello, Alice. You are 30 years old.

Data validation is the runtime process where we are checking whether the data in the input is of the correct type.

def greet(name, age):

if not isinstance(name, str):

raise ValueError(f"Name has to be str, got {type(name)}")

if not isinstance(age, int):

raise ValueError(f"Age has to be int, got {type(age)}")

return f"Hello, {name}. You are {age} years old."

message = greet(30, "Alice")

#Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "<python-input-2>", line 1, in <module>

# greet(30, "Alice")

# ~~~~~^^^^^^^^^^^^^

# File "<python-input-0>", line 3, in greet

# raise ValueError(f"Name has to be str, got {type(name)}")

#ValueError: Name has to be str, got <class 'int'>

Why use type hints Link to heading

We already know that types in Python do not affect the runtime. So some may ask why bother using type hints in Python if they are ignored anyway?

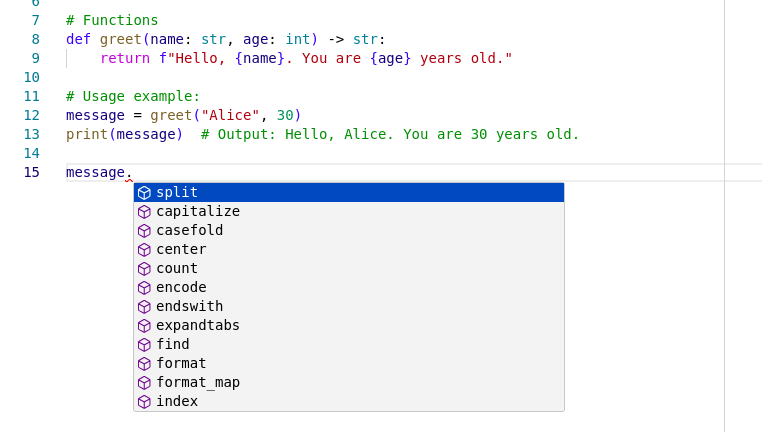

- Better development experience.

Modern IDEs can recognize types in our code and recommend possible methods:

- Improved code readability

- Fewer errors in the code (when combined with type checker)

- Self-documenting code

- Easier refactors

Last but not least, because type hints do not impact the runtime, it means that you don’t need to add all the possible types from the beginning. You can gradually add types as your program evolves, or when upgrading legacy code.

Simple Types Link to heading

Let’s start with the simple types called built-ins. Or in other languages they may be known as primitives. Although it is convenient to think about them as primitives, remember that everything in Python is an object! This is just to help our imagination. They are not real primitives.

Table 1.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

int |

integer |

float |

floating point number |

bool |

boolean value (subclass of int) |

str |

text, sequence of unicode codepoints |

bytes |

8-bit string, sequence of byte values |

object |

an arbitrary object (object is the common base class) |

Example:

# Variables

age: int # Type hint without value assignment

# This creates only an entry in the __annotations__

# dictionary, the variable does not exist!

# age = 25 # Value assigned later

# Functions

def greet(name: str, age: int) -> str:

return f"Hello, {name}. You are {age} years old."

# Usage example:

message = greet("Alice", 30)

print(message) # Output: Hello, Alice. You are 30 years old.

Type hinting a variable before assigning a value to it is useful in some cases, for example when unpacking:

# Source: mypy.readthedocs.io

# for mypy to infer the type of "cs" from:

a, b, *cs = 1, 2 # error: Need type annotation for "cs"

rs: list[int] # no assignment!

p, q, *rs = 1, 2 # OK

Annotating empty collections:

# Source: mypy.readthedocs.io

l: list[int] = [] # Create empty list of int

d: dict[str, int] = {} # Create empty dictionary (str -> int)

But list and dict are not on our list of basic types. But before diving beyond basic types, let’s pause and talk about type checkers, as they are going to be very useful for us.

Type checkers Link to heading

Type checkers are programs that read the code and validate if the types are correctly annotated. They raise errors if something is wrong. Their usage can help detect bugs earlier, before running the code.

Popular Type checkers Link to heading

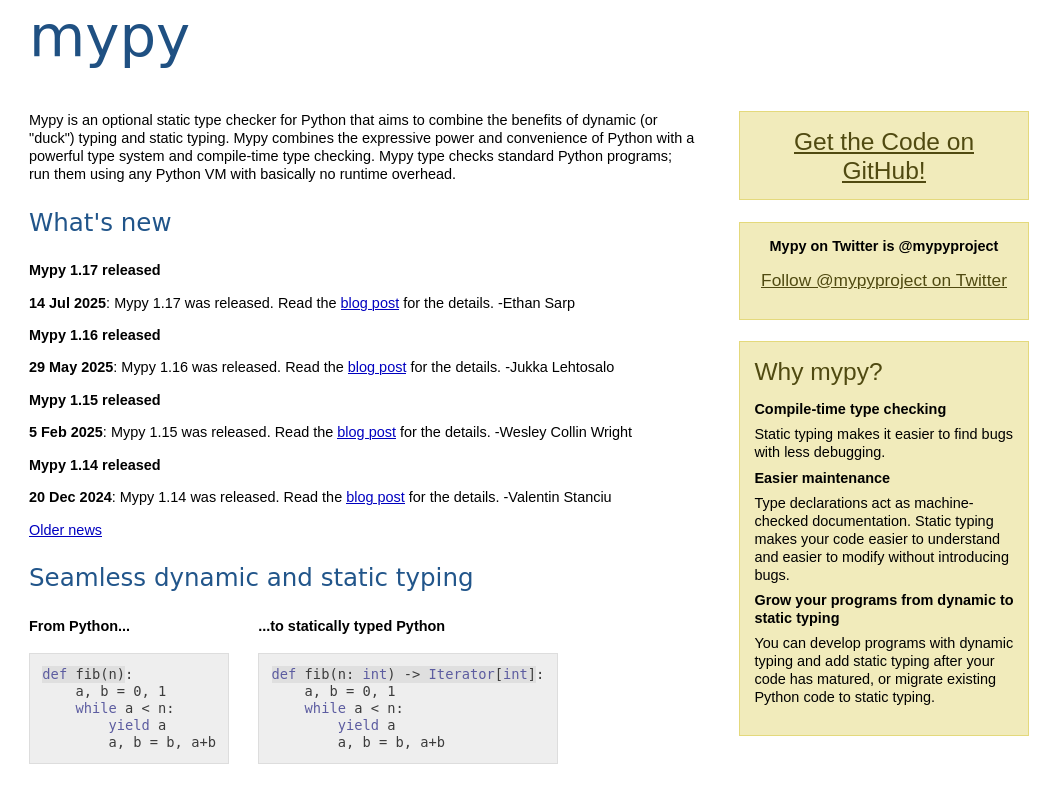

MyPy is one of the oldest and most renowned type checkers in the Python world. It can be considered the golden standard.

In this article, I’m going to focus on and use only MyPy.

MyPy Link to heading

Source: https://www.mypy-lang.org

Pyright Link to heading

If you are using the Pylance extension in VS Code, then you are also using Pyright, maybe even without knowing it, because Pylance incorporates Pyright.

Source: https://microsoft.github.io/pyright/

ty Link to heading

A new type checker from the Astral company, which gave us very good and popular tools like ruff and uv.

Still in beta, but I recommend keeping an eye on it, because if it turns out to be as good as their other tools, it may become very popular in the future.

Source: https://docs.astral.sh/ty

Beyond basics Link to heading

Going back to types, unfortunately in bigger programs it quickly becomes obvious that simple types are not enough. Fortunately, Python provides many generic types ready to use.

Generic Types Link to heading

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

list[str] |

list of str objects |

tuple[int, int] |

tuple of two int objects (tuple[()] is the empty tuple) |

tuple[int, ...] |

tuple of an arbitrary number of int objects |

dict[str, int] |

dictionary from str keys to int values |

Iterable[int] |

iterable object containing ints |

Sequence[bool] |

sequence of booleans (read-only) |

Mapping[str, int] |

mapping from str keys to int values (read-only) |

type[C] |

type object of C (C is a class/type variable/union of types) |

Other popular generic types include:

CallableGenerator

Generic types like list, tuple, and dict are ready to use immediately. Others need to be imported from the collections.abc module.

from collections.abc import Callable, Iterable

def process_people(

people: Iterable[tuple[str, int]],

transform: Callable[[tuple[str, int]], tuple[str, int]],

) -> list[tuple[str, int]]:

"""Applies the transform function on each person tuple and returns a dictionary

with original and transformed lists."""

return [transform(person) for person in people]

# Example usage:

people = [("Alice", 30), ("Bob", 25)]

def celebrate_birthday(person: tuple[str, int]) -> tuple[str, int]:

name, age = person

return (name, age + 1)

result = process_people(people, celebrate_birthday)

print(result)

It is worth mentioning that before Python 3.9, all generic types had to be imported from the typing module, and list, dict, and tuple had to be used as List, Dict, and Tuple, with the first letter capitalized.

Some of you may notice that I used Iterable instead of list for the people parameter. This exemplifies an important rule when annotating:

Always use as general types as possible for inputs, and return as specific types as possible.

Iterable is more general than list. It refers to all objects that implement the __iter__ method. In further examples, you will see that I switched from list to tuple and the code still passes the type check. Someone could even create a custom object that implements __iter__ and again pass the check. Such an approach gives us much more flexibility to refactor code or to use third-party code.

At the same time, process_people returns a very specific list[tuple[str, int]]. Because the type is specific, you know exactly what operations can be performed on it. For example, if it were Iterable, you wouldn’t know if it is safe to use methods like remove, because it works on lists but not on tuples!

Aliases Link to heading

As we progress with our annotations and use more advanced generic types, careful readers probably notice that Callable[[tuple[str, int]], tuple[str, int]] becomes less readable.

In such situations, aliases come in handy.

Example:

from collections.abc import Callable, Iterable

Person = tuple[str, int]

def process_people(

people: Iterable[Person],

transform: Callable[[Person], Person],

) -> list[Person]:

"""Applies the transform function on each person tuple and returns a dictionary

with original and transformed lists."""

return [transform(person) for person in people]

people = [("Alice", 30), ("Bob", 25)]

def celebrate_birthday(person: Person) -> Person:

name, age = person

return (name, age + 1)

result = process_people(people, celebrate_birthday)

print(result)

In newer version of Python (>3.12):

type Person = tuple[str, int]

And in Python 3.10, the TypeAlias was introduced:

from typing import TypeAlias

Person: TypeAlias = tuple[str, int]

Classes Link to heading

Operating on tuples can be very limiting. To contain data (and behavior, though not in this example), classes are perfect.

We can make the code even clearer.

from collections.abc import Callable, Iterable

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int) -> None:

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{type(self).__name__}(name={self.name}, age={self.age})"

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return self.__str__()

def process_people(

people: Iterable[Person],

transform: Callable[[Person], Person],

) -> list[Person]:

"""Applies the transform function on each person tuple and returns a dictionary

with original and transformed lists."""

return [transform(person) for person in people]

people = (Person("Alice", 30), Person("Bob", 25)) # tuples are also Iterables!

def celebrate_birthday(person: Person) -> Person:

person.age += 1

return person

result = process_people(people, celebrate_birthday)

print(result)

Dataclasses Link to heading

To go one step further, we can change the Person class to a dataclass. Dataclasses are perfect for small objects that mostly encapsulate data. They give us very concise syntax, and under the hood add all the boilerplate for us.

from collections.abc import Callable, Iterable

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

age: int

def process_people(

people: Iterable[Person],

transform: Callable[[Person], Person],

) -> list[Person]:

"""Applies the transform function on each person tuple and returns a dictionary

with original and transformed lists."""

return [transform(person) for person in people]

people = [Person("Alice", 30), Person("Bob", 25)]

def celebrate_birthday(person: Person) -> Person:

person.age += 1

return person

result = process_people(people, celebrate_birthday)

print(result)

Any Link to heading

Any is a special type that can represent anything. Because of that, everything is allowed with Any. Anything can be assigned to Any, and Any can be assigned to anything. All methods, operations, etc., are allowed on Any.

But be careful with Any, because it allows you to fool the type checkers. If used incorrectly, it can silence issues that may come up later as errors.

from typing import Any

#Source: mypy.readthedocs.io

a: Any = None

s: str = ''

a = 2 # OK (assign "int" to "Any")

s = a # OK (assign "Any" to "str")

Personally, I find Any useful when you literally don’t care about the content of the container object like list.

def get_len(it: list[Any]) -> int:

return len(it)

The above example does not have much practical value, but it conveys the idea. In this case, it literally does not matter what kinds of objects are inside the it list.

Unions and Optionals Link to heading

Now, you already have a lot in your type hints arsenal. But what if you need something more unique, or the argument passed to the function can be one of multiple types?

Here, unions and optionals come in handy.

def find_person(people: Iterable[Person], name: str) -> Person | None:

for person in people:

if person.name == name:

return person

def greet_person(person: Person, greeting: str | None = None) -> str:

if greeting is None:

greeting = "Hello"

return f"{greeting}, {person.name}!"

Before Python 3.10, you can find an older syntax:

from typing import Union, Optional

def find_person(people: Iterable[Person], name: str) -> Union[Person, None]:

...

def greet_person(person: Person, greeting: Optional[str] = None) -> str:

...

Ellipsis Link to heading

In the examples above, you may have noticed the ... (three dots) inside the function bodies.

Three dots are a special syntax for the Ellipsis object.

It’s a special object in Python that does nothing. It is unique in a Python program (similar to None), and it is common to see it in examples or stub files.

Python syntax requires something in a function or class body. When you want to create a function or class without defining its body and avoid syntax errors, you can use Ellipsis.

The main difference between Ellipsis and the pass keyword is this: Ellipsis is an object, while pass is a keyword that allows skipping the function or class body.

Whether to use pass or Ellipsis is often up to personal preference. Unfortunately, except in stub files, there is no guideline on which to use. The most important thing is to be consistent, and if you mix both, then add guidelines to your project explaining when you use each.

Besides examples and empty functions or classes, Ellipsis has one more practical usage in type hints.

In container types like tuple, it can indicate that the tuple has an unspecified length of certain types.

# This means that the people is a tuple with just ONE element of type Person.

# Often it is not what we want'

people: tuple[Person]

# Now this means that the people is a tuple with unspecified numbered of elements.

# But all of those elements are of type Person

people: tuple[Person, ...]

We can also use Ellipsis in Callable to specify the unknown number of arguments that the callable accepts.

def handle_person_action(action: Callable[..., None], person: Person) -> None:

action(person)

def greet(person: Person) -> None:

print(f"Hello, {person.name}!")

person = Person("Alice", 30)

# Using the handler with different callables

handle_person_action(greet, person) # Outputs: Hello, Alice!

handle_person_action(lambda x: print(f"Person is {x.name}"), person) # Outputs: Person is Alice

Generics Link to heading

You already know generic types like list, tuple, dict, Iterable, Callable, etc. But what if you would like to create your own generic type?

Python supports that. You can create a generic function that accepts a generic type:

from typing import TypeVar

T = TypeVar('T') # We define a generic variable

def get_first_element(items: list[T]) -> T:

return items[0]

print(get_first_element([1, 2, 3])) # Output: 1

print(get_first_element(["apple", "banana", "cherry"])) # Output: apple

Or even a generic class:

from typing import TypeVar, Generic

T = TypeVar('T')

class Box(Generic[T]):

def __init__(self, content: T):

self.content = content

def get_content(self) -> T:

return self.content

int_box = Box[int](123)

print(int_box.get_content()) # Output: 123

str_box = Box[str]("Hello")

print(str_box.get_content()) # Output: Hello

In Python 3.12 and above, you can find newer syntax:

def get_first_element[T](items: list[T]) -> T: ...

class Box(Generic[T]): ...

Examples here are not particularly useful—especially the one with a generic function. In my experience, generics are used only in very specific situations. The problem with them is that they need to be very general because you don’t know the exact type that will be passed (although there are ways to narrow them down). Usually, we need specific types because it makes type checking easier and code safer. Nevertheless, there are rare cases when generics are useful, so it’s worth being aware of their existence.

Abstract Base Classes Link to heading

In Python, Abstract Base Classes (ABCs) are similar to other languages like Java but also differ in some ways. They allow creating a base class that cannot be instantiated and can only be used as a parent for other classes. But just like regular classes, subclasses of an abstract class inherit all its attributes. In a way, they are like interfaces where we define what methods need to be implemented by the subclass.

Subclasses have to implement methods decorated with @abstractmethod in the abstract class. If a subclass doesn’t implement them, it becomes abstract itself.

What may differ from other languages is that abstract classes can share their logic with subclasses, define regular (non-abstract) methods, and even allow calling methods decorated with @abstractmethod from subclasses (though this is not recommended).

A simple example makes this clearer.

import abc

class Animal(abc.ABC):

@abc.abstractmethod

def speak(self) -> str: ...

class Dog(Animal):

def speak(self) ->str:

return "Woof!"

class Cat(Animal):

def speak(self) -> str:

return "Meow!"

def animal_sound(animal: Animal) -> None:

print(animal.speak())

dog = Dog()

cat = Cat()

animal_sound(dog) # Output: Woof!

animal_sound(cat) # Output: Meow!

I used this code initially to show duck typing. Here we still use duck typing but with Abstract Base Classes we can annotate an animal parameter in the animal_sound function to be of the type Animal. Now type checkers like mypy will check if the object passed to the function is of the correct type, thus if it has a speak method.

Protocols Link to heading

Protocols use something professionally called “Structural Sub-typing”. That means checking if an object conforms to a structure.

There is no need for inheritance! Because of that, Protocols give you a lot of flexibility.

import typing

class Speaker(typing.Protocol):

def speak(self) -> str: ...

class Dog:

def speak(self) ->str:

return "Woof!"

class Cat:

def speak(self) -> str:

return "Meow!"

def talk(speaker: Speaker) -> None:

print(speaker.speak())

dog = Dog()

cat = Cat()

talk(dog) # Output: Woof!

talk(cat) # Output: Meow!

Speaker defines the method speak, but only its signature (name, parameters with types, and return type). The function body contains only Ellipsis.

Similarly to abstract classes, type checkers will verify if the object passed to the talk function has a speak method. If it does, it will be considered a subclass of Speaker, thus a valid type.

ABC vs Protocols Link to heading

When to use which? As usual, there is no strict simple answer. Here I can only share my opinion about the pros and cons of both and when I prefer one over the other.

Abstract Base Classes explicitly force developers to follow the interface you define. I find this very useful when using them for internal parts of an application not exposed publicly. This means if you write a library others import as a third-party dependency, then protocols are a much better fit. Usually, you don’t want others to inherit from some internal abstract classes just to pass a type check.

Protocols are also good if you want to define attributes on the class.

import typing

class Speaker(typing.Protocol):

sound: str

def speak(self) -> str: ...

This way, we define that Speaker protocol-compatible classes need to implement both the sound attribute and the speak method. This can’t be achieved as elegantly with abstract classes. Abstract classes only verify the existence of methods. To achieve the same effect in ABCs, you would need to use the @property decorator:

import abc

class Animal(abc.ABC):

@abc.abstractmethod

def speak(self) -> str: ...

@property

@abc.abstractmethod

def sound(self) -> str: ...

But that means all Animal subclasses have to implement sound as a method.

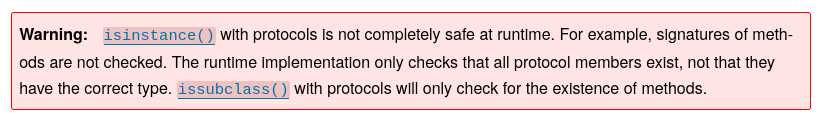

On the other hand, an advantage of abstract classes is that they are easily runtime-checkable with functions like isinstance. This can also be achieved with protocols using the @runtime_checkable decorator, but even the official documentation warns against using it.

Comparison Link to heading

| Abstract Base Class | Protocol | |

|---|---|---|

| flexibility | Not very flexible, requires explicit inheritance | Very flexible due to structural sub-typing |

| where to use | Good for internal classes | Good for public APIs |

| attributes support | Does not support attributes, but this can be worked around with @property |

Supports attributes |

| runtime checkable | Yes, runtime checkable | Yes, but with limited support |

Extra Link to heading

As a small extra example, nothing stops us from combining abstract classes and protocols in the same class. More accurately, we are using protocols inside an abstract class. Still, this example is very interesting.

import abc

import typing

class Config(typing.Protocol):

name: str

class Platform(abc.ABC):

config = Config

def __init_subclass__(cls, /, config: type[Config], **kwargs):

super().__init_subclass__(**kwargs)

cls.config = config

@abc.abstractmethod

def get_name(self) -> str:

...

class SonyConfig:

name = "Sony"

class Sony(Platform, config=SonyConfig):

def get_name(self) -> str:

return self.config.name

if __name__ == "__main__":

sony = Sony()

name = sony.get_name()

print(name)

Problems Link to heading

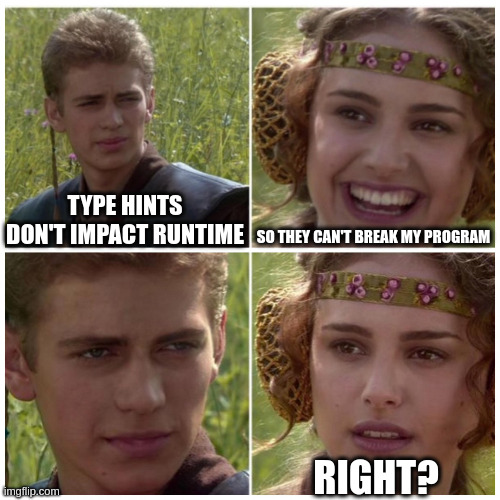

Type Hints don’t impact runtime, … right? Link to heading

I heard that so many times, that I started to believe it. And in a way, it is true. Indeed, types do not impact runtime, as they don’t matter for the Python interpreter. This is something I tried to explain with the custom Int and Str classes at the beginning.

So where’s the problem? Python is constructed so that everything after a colon in the function signature parameters is valid Python code that can be evaluated. That means things there can break on the evaluation level.

def create_message(person: Person | None = None) -> str:

if person is None:

return "Generic message to everyone"

return f"Personalized message to {person.name}"

class Person: ...

This example fails because we try to use the object Person which is not yet defined. Python is an interpreted language, and when the interpreter reads the signature of the create_message function, it knows nothing about Person.

NameError: name 'Person' is not defined

There are 2 solutions for that. First, we can move create_message below the definition of the Person class. But sometimes we cannot or don’t want to do that. That’s why there is a second way: to use a string literal as a type. When using string literals, type checkers and IDEs still understand that it is a Person object type, and at the same time, for the interpreter it is just a string, so it won’t complain about NameError.

def create_message(person: "Person" | None = None) -> str:

if person is None:

return "Generic message to everyone"

return f"Personalized message to {person.name}"

class Person: ...

But now we hit another issue that I personally commit quite often. The union operator | cannot operate between a string and another object!

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for |: 'str' and 'NoneType'

So as you can see, type hints don’t affect runtime, … until they do.

The solution is either to put everything into a string or to use the older Union type.

def create_message(person: "Person | None" = None) -> str: ...

from typing import Union

def create_message(person: Union["Person", None] = None) -> str: ...

Future Link to heading

There is a special module in Python called __future__. It is rarely used, but sometimes useful. The creators of Python put features there that may alter the standard behavior of Python. One of those features is annotations.

from __future__ import annotations

When the above line appears at the very top of the imports, it changes how Python evaluates annotations. Now all annotations become strings!

OK, cool, but why use it? In bigger projects where packages import objects from one another, it is easy to fall into the issue of circular imports. In a naive example, when module A imports function b from module B, and module B imports function a from module A, we get a circular import error.

This looks like this:

A -> b (from B) -> a (from A) Error!

Such imports are rather easy to find even before running the code. That’s why usually circular imports happen in bigger projects where it’s harder to track dependencies:

A -> b (from B) -> c (from C) -> d (from D) -> b (from B)

It can be even more difficult and annoying when we import things in the package __init__.py file.

One way to solve this issue (there are more, but this is not an article about circular imports) is to use the TYPE_CHECKING constant. Often, we import things only for annotations; we do not use them otherwise. TYPE_CHECKING is a special variable that is true only when type checkers validate the code. So we can put the import behind this check:

from typing import TYPE_CHECKING

if TYPE_CHECKING:

from people import Person

def create_message(person: Person | None = None) -> str: ...

But now we get:

NameError: name 'Person' is not defined

Because we import Person only for type checks, during runtime this code is evaluated and Python does not see Person in scope.

That’s why we want to use from __future__ import annotations, because now even during runtime, it will be just a string literal that does nothing at runtime.

from __future__ import annotations

from typing import TYPE_CHECKING

if TYPE_CHECKING:

from people import Person

def create_message(person: Person | None = None) -> str: ...

Other typing features Link to heading

Many of the following features are not available in older versions of Python. But there is a way to use them. The package typing_extensions was created to support new typing features in older Python versions.

Overload Link to heading

Better annotations come into play when types become more complex. Sometimes methods can return different types depending on what arguments are passed. In the example below, the get_info method can return either a string, an integer, or a tuple of string and integer. But the function’s logic clearly distinguishes which type will be returned depending on the arguments.

Overloading allows you to narrow down the types and make the annotation more precise.

from typing import overload, Literal, Union, Tuple, Self

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int) -> None:

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{type(self).__name__}(name={self.name}, age={self.age})"

def celebrate_birthday(self) -> Self:

self.age += 1

return self

def change_name(self, new_name: str) -> Self:

self.name = new_name

return self

# Overloads for better type hints

@overload

def get_info(self, detail: Literal["name"]) -> str: ...

@overload

def get_info(self, detail: Literal["age"]) -> int: ...

@overload

def get_info(self) -> Tuple[str, int]: ...

# Actual implementation (only one real function)

def get_info(self, detail: Union[Literal["name"], Literal["age"], None] = None) -> Union[str, int, Tuple[str, int]]:

if detail == "name":

return self.name

elif detail == "age":

return self.age

else:

return (self.name, self.age)

person = Person("Alice", 30)

print(person.get_info()) # Outputs: ('Alice', 30)

print(person.get_info("name")) # Outputs: 'Alice'

print(person.get_info("age")) # Outputs: 30

Override Link to heading

For extra safety, you can use the @override decorator. It has a couple of benefits. First, it protects you from typos, which can lead to unexpected and hard-to-find bugs because your class will still work, but the method you think is being called is not. Instead, Python will use a method from the parent class.

Apart from catching typos, it also automatically documents your code and makes it easier for others to understand. I know that IDEs like PyCharm can provide the same information, but that ties you to a specific IDE, while people use various code editors at work. Plus, with a decorator, you can integrate MyPy or other type checkers into your CI process.

import abc

from typing import override

class Animal(abc.ABC):

@abstractmethod

def speak(self) -> str: ...

class Dog(Animal):

@override

def speak(self) ->str: ...

class Cat(Animal):

def speak(self) -> str: ... # Error! (becasue we didn't use @override)

class Fish(Animal):

@override

def speek(self) -> str: ... # Error! (because of typo in speak)

But this doesn’t work by default. You need to set specific type checker settings or add an extra flag like --enable-error-code explicit-override or --strict.

Self Link to heading

A convenient way to annotate that a method returns an instance of its own class.

from typing import Self

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int) -> None:

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{type(self).__name__}(name={self.name}, age={self.age})"

def celebrate_birthday(self) -> Self:

self.age += 1

return self

def change_name(self, new_name: str) -> Self:

self.name = new_name

return self

person = Person("Alice", 30)

person.celebrate_birthday().change_name("Rachel")

print(person) # Outputs: Person(name=Rachel, age=31)

This was introduced in Python 3.11. Before Self, to achieve the same thing you needed to use a string literal:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int) -> None: ...

def __str__(self) -> str: ...

def celebrate_birthday(self) -> "Person": ...

def change_name(self, new_name: str) -> "Person": ...

MyPy Misc Link to heading

Flags Link to heading

Not all checking features are available by default in MyPy. Here are a few flags that I find useful when working with types:

-

This flag makes MyPy raise an error when a function is not annotated. By default, MyPy treats all local variables inside an unannotated function and its return type as

Any. Because of that, this basically means no type checking for such functions. -

--enable-error-code explicit-overrideAs mentioned earlier, this flag enables recognition of the

@overridedecorator. Without it, you don’t get any benefits from using@override, so it’s important to remember to enable it if you want to use the@overridefeature. -

--strictThis flag activates very strict checking by combining many extra rules that are disabled by default. For example, the previously mentioned flags are included when using

--strict.

ignore Link to heading

There are situations where we cannot do much about types. No matter how we try, some parts of the code cannot be properly annotated. This happens, for example, when using third-party libraries that are not annotated or in test code, where the typing rules are slightly different.

In such moments, # type: ignore comes in handy. MyPy will ignore type checking for the line that contains a comment with the word ignore.

Personally, I like to use # type: ignore when importing modules that don’t support typing:

import requests # type: ignore[import-untyped]

However, I do not recommend using a bare # type: ignore because it makes MyPy ignore all errors on that line. Instead, you can provide a specific error code to ignore inside square brackets.

By the way, I was also surprised that a package like requests is not annotated by default. Fortunately, it provides a package called types-requests containing stub files with annotations.

What are stub files? These are special files that contain only the signatures of functions, classes, methods, and variables with annotations but without actual implementations. They can be used by type checkers like MyPy. For those familiar with C/C++, stubs are similar to header files.

References Link to heading

General

- Type Theory: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_theory

- Type System: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_system

- Data Type: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_type

- A brief history of “type”: https://arcanesentiment.blogspot.com/2015/01/a-brief-history-of-type.html

Python

- PEP-484: https://peps.python.org/pep-0484/

- Static Typing with Python: https://typing.python.org/en/latest/#

- Python typing module: https://docs.python.org/3/library/typing.html

- Python Data Model: https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html

- Mypy docs: https://mypy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/cheat_sheet_py3.html

- FastAPI Python types: https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/python-types

- RealPython Type Checking: https://realpython.com/python-type-checking

- Lazy annotations: https://realpython.com/python-annotations/

- EAFP vs LBYL: https://realpython.com/python-lbyl-vs-eafp/

YouTube Videos

- Python Tutorial: Type Hints - From Basic Annotations to Advanced Generics

- Python Tutorial: Duck Typing and Asking Forgiveness, Not Permission (EAFP)

- PyWaw #117 What NOT TO DO when type hinting in Python?

Code Examples: